European Martial Arts Through Time

European martial arts have a rich history that spans thousands of years, with distinct traditions developing across different regions and time periods. Unlike Asian martial arts, which often maintained continuous traditions, European martial arts experienced periods of evolution, transformation, and sometimes discontinuity. Here’s how they can be traced and catalogued through different historical periods:

Ancient Period (800 BCE – 500 CE)

- Greek Pankration and Wrestling: Documented in pottery, sculptures, and texts like Homer’s works

- Roman Gladiatorial Combat: Detailed in mosaics, reliefs, and writings by Suetonius and others

- Celtic and Germanic Tribal Combat: Primarily known through archaeological finds and Roman accounts

Early Medieval Period (500-1000 CE)

- Viking Combat Styles: Evidenced in sagas, archaeological finds, and burial goods

- Early Knights and Mounted Combat: Beginning of formalized mounted warfare techniques

- Byzantine Military Traditions: Preserved much of Roman military knowledge in manuals like the Strategikon

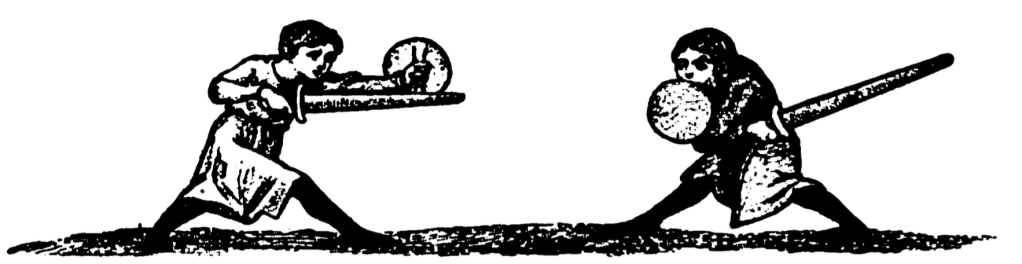

High Middle Ages (1000-1300 CE)

- Development of Knightly Combat: Formalization of armored combat with lance, sword, and shield

- Tournament Fighting: Evolution from chaotic melees to more structured combat sports

- Early Fencing Traditions: Beginning of systematic swordsmanship outside of battlefield contexts

Late Medieval Period (1300-1500 CE)

- Fechtbücher Tradition: First systematic martial arts manuals appear (I.33 Manuscript, ~1300)

- Prominent Masters: Johannes Liechtenauer, Fiore dei Liberi, Hans Talhoffer created influential systems

- Guild Systems: Formation of fighting guilds like the Brotherhood of St. Mark (Marxbrüder)

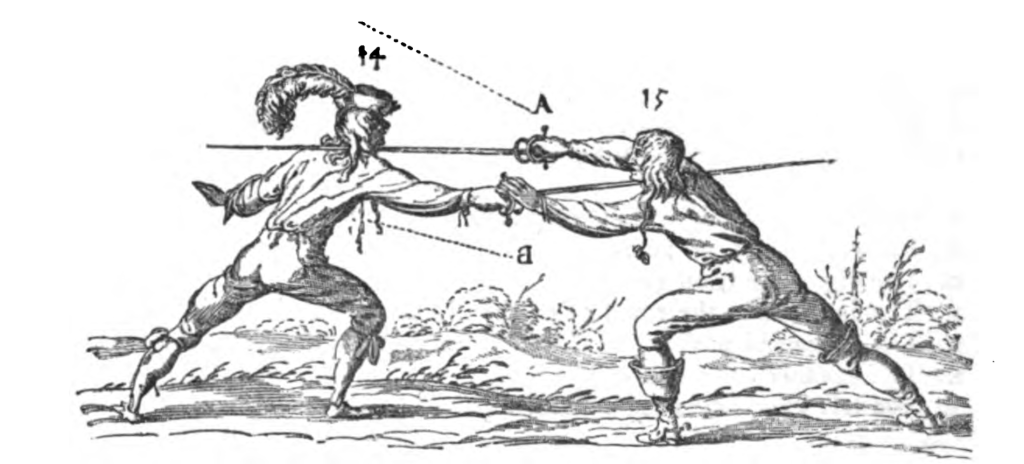

Renaissance Period (1500-1700 CE)

- Rapier Fighting: Evolution toward civilian dueling and self-defense

- National Schools: Development of distinct Italian, Spanish, German, and English styles

- Scientific Approach: Application of geometric principles and mechanics to fencing (Camillo Agrippa)

Enlightenment to Modern Era (1700-1900 CE)

- Smallsword and Dueling: Refinement of lighter weapons and emphasis on precision

- Military Saber Systems: Formalized cavalry combat systems

- Sport Evolution: Transition toward modern fencing with protective equipment

- Boxing and Wrestling Codification: Formalization of rules for unarmed combat sports

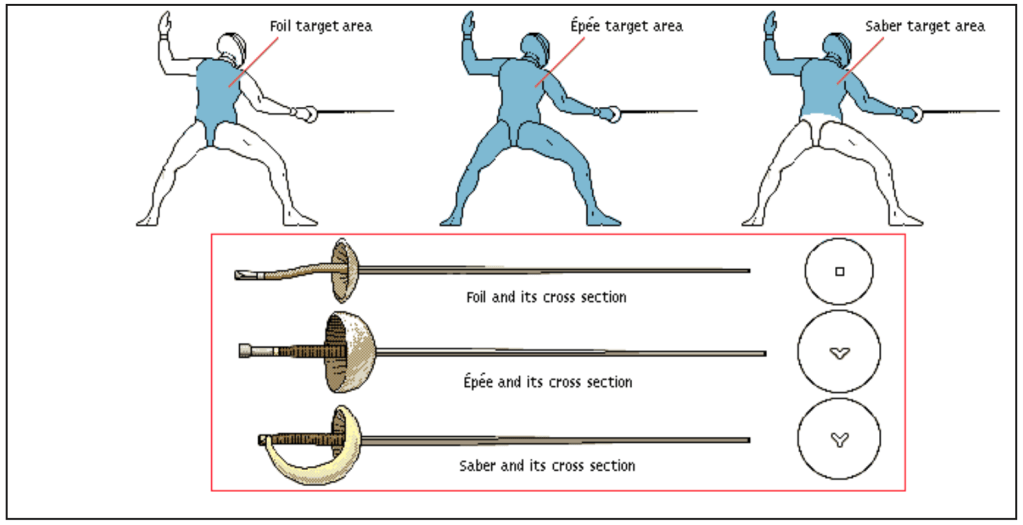

Modern Period (1900-Present)

- Olympic Fencing: Standardization of foil, épée, and saber as sport disciplines

- HEMA Revival: Historical European Martial Arts reconstruction movement based on historical texts

- Military Combatives: Development of military hand-to-hand combat systems

What makes the study of European martial arts particularly fascinating is the rich documentation through fighting manuals (fechtbücher), artwork, and literary sources that allow modern practitioners to reconstruct these historical fighting systems with considerable accuracy.

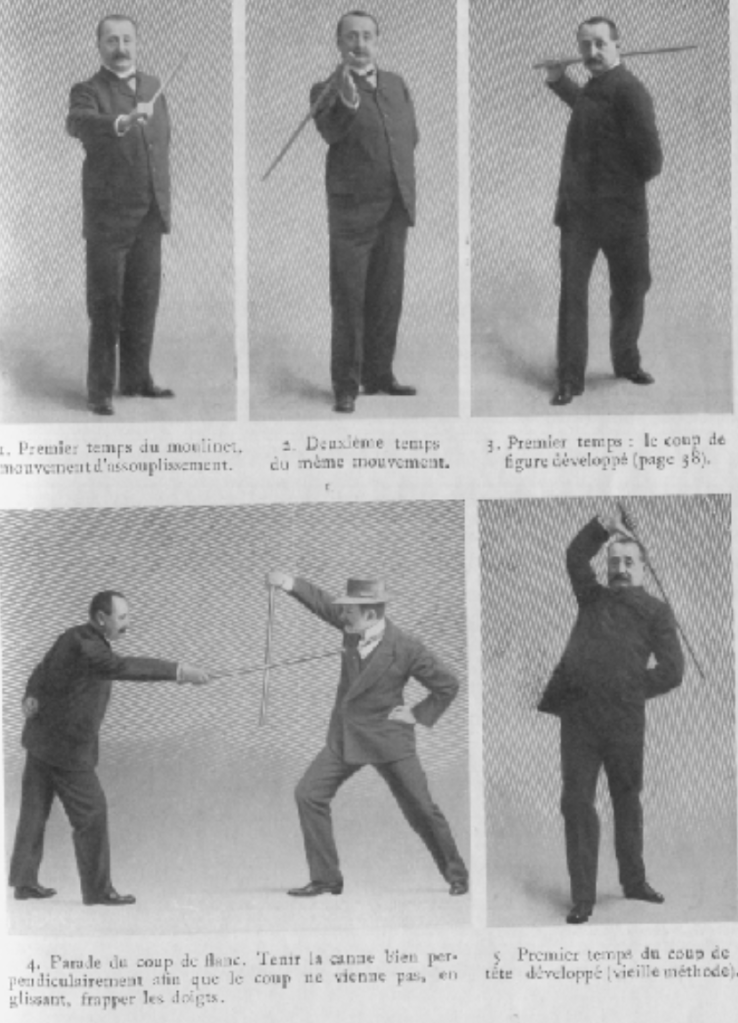

La Canne: Walkingstick Fencing

La Canne (or Canne de Combat) would primarily be placed in the 19th and early 20th century European martial arts timeline, though it has roots in earlier periods and continues as a modern sport today.

Historical Placement

Origins (18th Century)

- La Canne evolved from earlier stick fighting methods used throughout Europe

- Influenced by French naval tradition where sailors used sticks for training and self-defense

Formalization (19th Century)

- Primary Development Period: Mid-to-late 19th century France

- Context: Urban self-defense during a period when gentlemen regularly carried walking sticks

- Connection to Savate: Often taught alongside French kickboxing (Savate) in the same academies

- Defensive Focus: Developed as a practical civilian self-defense method, not primarily a sport

Belle Époque Peak (1880-1914)

- Reached peak popularity during this period

- Became an integral part of French martial culture

- Featured in physical education and military training

La Canne represents an interesting transition between traditional European martial arts and modern combat sports, bridging aristocratic fencing traditions with practical civilian self-defense during a time of changing social norms and weapons technology.

Charles Charlemont: Key Figure in French Martial Arts

Charles Charlemont (1862-1944) should be placed in the late 19th to early 20th century period of European martial arts development, specifically within the French martial arts tradition. He was a pivotal figure in both Savate (French kickboxing) and La Canne de Combat (French stick fighting).

Historical Context for Charlemont

Late 19th Century French Martial Arts (1870s-1910s)

- Period of Systematization: When traditional street fighting methods were being formalized into structured combat systems

- Belle Époque Paris: Urban setting where martial arts were becoming both combat systems and spectator sports

- Transition Era: Between purely practical combat methods and modern sport forms

Historical Significance

Charlemont represents a critical juncture in martial arts history when traditional European fighting systems were being preserved through sportification during a period when firearms and changing social norms were making many traditional combat skills obsolete for practical self-defense.

He bridges the gap between the older, more combat-oriented traditions of stick fighting and the modern sport version of La Canne that continues today, making him an important figure in the late period of traditional European martial arts development and the early period of modern European combat sports.Retry

Comparing Tomiki Aikido with La Canne

La Canne (or Canne de Combat) offers a fascinating parallel to Tomiki Aikido when examining Asian and European martial arts systems. La Canne merits specific attention due to its formalized structure and sporting aspects that make it particularly comparable to Tomiki’s approach.

Historical Context and Development

Tomiki Aikido:

- Developed in the mid-20th century by Kenji Tomiki (1900-1979)

- Built upon traditional Daito-ryu Aiki Jujutsu and Kodokan Judo principles

- Systematized for modern educational purposes after WWII

- Emphasizes both traditional forms and competitive practice

La Canne:

- Formalized in 19th century France, though with older roots in European stick arts

- Refined by fencing masters like Charles Charlemont and Joseph Charlemont

- Developed alongside savate (French kickboxing) as a self-defense system

- Modernized in the 20th century as a competitive sport through the Fédération Française de Savate et Canne

Both arts underwent significant modernization processes that transformed traditional combat techniques into formalized systems suitable for sporting contexts and physical education.

Technical Characteristics

Tomiki Aikido:

- Circular movements using the tegatana (hand blade)

- Techniques categorized into atemi-waza (striking) and kansetsu-waza (joint techniques)

- Emphasis on ma-ai (distance control) and kuzushi (breaking balance)

- Techniques flow from a separated stance (rikaku)

La Canne:

- Linear and circular strikes with a cane

- Techniques categorized into strikes (coups), parries (parades), feints (feintes) and counter attacks (ripostes)

- Strong emphasis on distance management and footwork derived from fencing

Competitive Frameworks

Tomiki Aikido:

- Randori competition with tanto (knife) and empty-handed formats

- Scoring based on successful application of techniques and control

- Emphasis on proper form and execution rather than power

- Rules designed to preserve traditional principles while allowing for objective testing

La Canne:

- Modern competition (since 1970s) conducted in a marked area

- Points awarded for clean strikes to valid target areas (head, flanks, legs)

- Techniques must demonstrate extension, commitment, and control

- Protective equipment (mask, gloves, padded vest) allows for dynamic exchanges

Both systems developed competitive frameworks that allow practitioners to test skills while maintaining safety. However, La Canne competition more closely resembles fencing with its emphasis on scoring hits, while Tomiki Aikido competition focuses on successful application of controlling techniques.

Educational Philosophy

Tomiki Aikido:

- Progression from kata (forms) to randori (free practice) to shiai (competition)

- Techniques taught through “Basic Forms” and “Applied Techniques”

- Emphasis on understanding principles of balance and body mechanics

- Goal of personal development through technical mastery

La Canne:

- Progressive training from basic strikes to combinations to tactical applications

- Techniques taught through set drills and partner exercises

- Strong emphasis on athleticism, coordination, and precision

- Traditionally viewed as complementary to savate training

Cultural Integration

Tomiki Aikido:

- Explicitly connects practice to concepts like wa (harmony) and mushin (no-mind)

- Distinguishes between buryoku (military force) and bōryoku (violence)

- Incorporates traditional etiquette and dojo culture

- Progression follows shu-ha-ri model of traditional martial learning

La Canne:

- Embodies values of French physical culture and sporting tradition

- Less explicit philosophical framework beyond sporting ethics

- Maintains some traditional salutes and protocols derived from fencing

Methodological Similarities

Despite their different origins and techniques, both Tomiki Aikido and La Canne share significant methodological similarities:

- Systematization: Both were organized into coherent systems by educators seeking to preserve and transmit martial knowledge

- Pedagogical Structure: Both feature progressive teaching methods that build from fundamentals to advanced applications

- Competition as Tool: Both utilize competitive formats as educational tools while preserving technical standards

- Distance Management: Both place strong emphasis on proper distancing and timing

- Control over Power: Both prioritize precision and control over raw power or force

Conclusion

Tomiki Aikido and La Canne represent fascinating parallels in martial arts development across different cultural contexts. While developed independently and with different technical focuses, both systems demonstrate how traditional combat arts can be systematized, modernized, and adapted for contemporary educational and sporting purposes.

The primary difference lies in their philosophical underpinnings: Tomiki Aikido maintains stronger connections to traditional Japanese martial philosophy with concepts like harmony, balance, and spiritual development, while La Canne evolved more explicitly as a sporting practice with less emphasis on philosophical cultivation.

Both arts, however, successfully balance tradition with innovation, creating systems that preserve martial knowledge while making it accessible and relevant to modern practitioners—a testament to the universal impulse to develop, refine, and transmit martial arts across cultures and generations.