Introduction: Beyond the Mat – Exploring the Deeper Dimensions of Tomiki Aikido

It has been a while since I wrote about my thoughts on martial arts, particularly on Tomiki Aikido. Recent challenges regarding the use of Kenji Tomiki’s books as study tools have forced me to reconsider my involvement in this martial art. I find myself at a crossroads: I could simply disappear from the Tomiki Aikido scene, or I could take a different path—one that explores and articulates the ideas and concepts within Tomiki’s work that extend far beyond its competitive format.

This alternative approach views Tomiki Aikido not merely as a sport, but as a form of “performance art”—a practice that transcends the physical techniques and competitive aspects to touch something deeper about the nature of movement, conflict resolution, and human interaction. In this exploration, I aim to uncover the philosophical and artistic dimensions that make this martial art a vehicle for personal transformation and understanding.

Martial arts without Combat

The term “martial arts” contains an inherent contradiction that becomes increasingly apparent in modern practice. “Martial” derives from Mars, the Roman god of war, explicitly referencing violence and combat. Yet “art” suggests creativity, beauty, and human expression. This tension becomes acute when martial arts are practiced primarily as methods of self-defense, personal development, or artistic expression rather than actual combat preparation.

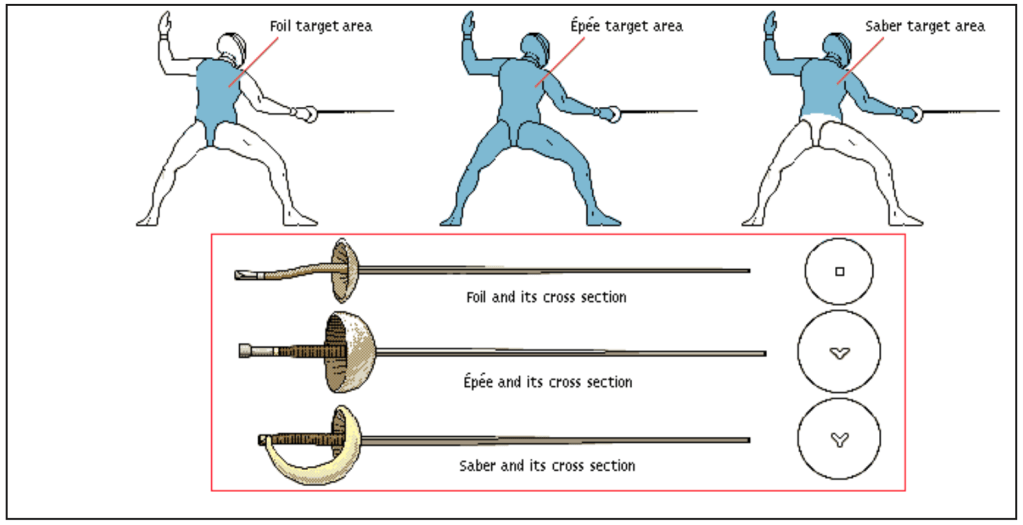

Does martial art belong to the realm of artistic experience, or is it fundamentally a sporting pursuit? From a purely functional standpoint, terms like “fighting system” or “combat method” might be more accurate, though these carry the negative associations of violence and aggression. However, when the fighting element is removed from “martial arts,” the functional foundation disappears entirely. What then remains of the original practice?

What remains when you remove the fighting:

1. Movement Philosophy

- Acting without forcing

- Spatial-temporal harmony

- Aesthetic and spiritual concepts that transcend the functional origin

2. Physical Culture

- Codified movement languages

- Ritual movement forms

- Aesthetics of precision, power, and grace

3. Philosophical Concepts

- Ethical codes in movement

- Contemplation through repetition

- Meditation in action

The Core of the Question

When you remove the fighting, an abstracted movement language remains – just as abstract painting no longer depicts “things” but becomes pure form.

The Different Approaches

Eastern Traditions

Eastern martial arts often owe their popularity to the abstracted movement language where movement is central and the functional aspect is a vague reflection of the original fighting method. As examples, we can mention Taichi, Aikido and Iaido. These movement forms still retain a vague perception of what was once a deadly fighting method. The functionality that must be characteristic of an efficient fighting method has practically disappeared entirely.

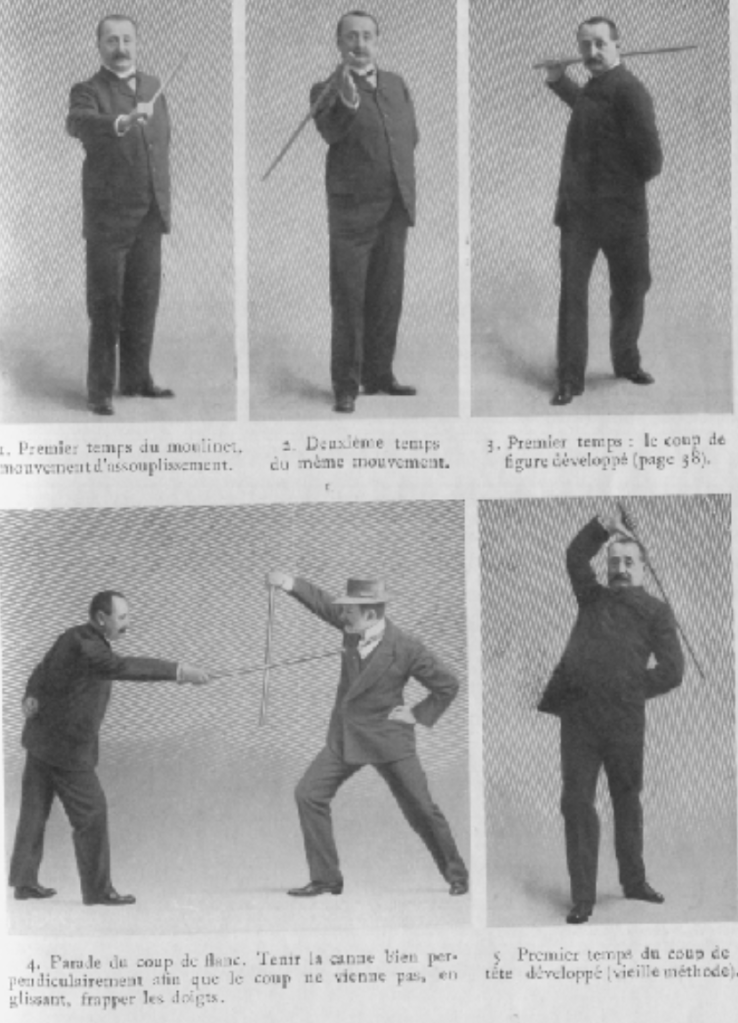

Performance Art

Performance art is a temporal, physical artistic practice in which the artist themselves is the primary medium. The body becomes a living artwork, time becomes material, and the liveness of the moment is essential.

Performance art remains radical because it resists the commodification of art by placing presence and temporality at its center. It is art that only exists in the moment of the encounter between performer and audience.

Demonstration Sport

Characteristics:

- Competitive but functionally not focused on efficiency in combat

- Spectacular for the audience through acrobatic actions

- Technical virtuosity in choreographed sequences

- Cultural legitimacy by referencing the origin

Sport Logic:

- Standardized rules and scoring systems

- Comparable performances

- Objective measurement systems

The Delusion of Efficiency in Martial Arts

A critical issue emerges when examining the claims of effectiveness made by various martial arts systems. It is important to distinguish dangerous-and-efficient fighting from safe-and-inefficient fighting, so that practitioners can easily understand what kind of activity they are engaging with, and can have realistic expectations about the effectiveness of it.

Many traditional martial arts that have undergone philosophical transformation continue to claim combat effectiveness while simultaneously removing the very elements that made them functional in real conflict. This creates a fundamental contradiction: systems marketed as “self-defense” or “martial arts” that have been systematically stripped of their martial applications.

The efficiency paradox manifests in several ways:

- Traditional forms performed with combat narratives despite having no pressure-testing against resistance

- Demonstration techniques that work only under choreographed conditions being presented as combat-applicable

- Philosophical frameworks used to justify the absence of realistic training while maintaining claims of martial effectiveness

- Cultural authority substituting for empirical verification of techniques

This delusion becomes problematic when practitioners genuinely believe they possess fighting skills that have never been tested under realistic conditions. The transformation from functional fighting system to performance art or personal development practice is legitimate, but the continued claims of combat effectiveness without corresponding training methodologies represents a fundamental misrepresentation of the art’s capabilities.

Do you like testing this way?

Some martial arts advertise a method useful for the street—brutal techniques tested and approved. The question arises in this case: are you ready to perform such a cruel action?