Early Life and Education (1900-1929)

Kenji Tomiki was born in March 1900 in Kakunodate, Akita Prefecture in northern Japan. He progressed through Kakunodate Elementary School and Yokote Prefectural Middle School before attending Waseda University’s Second Higher Academy. He ultimately graduated from Waseda University’s Faculty of Political Science and Economics.

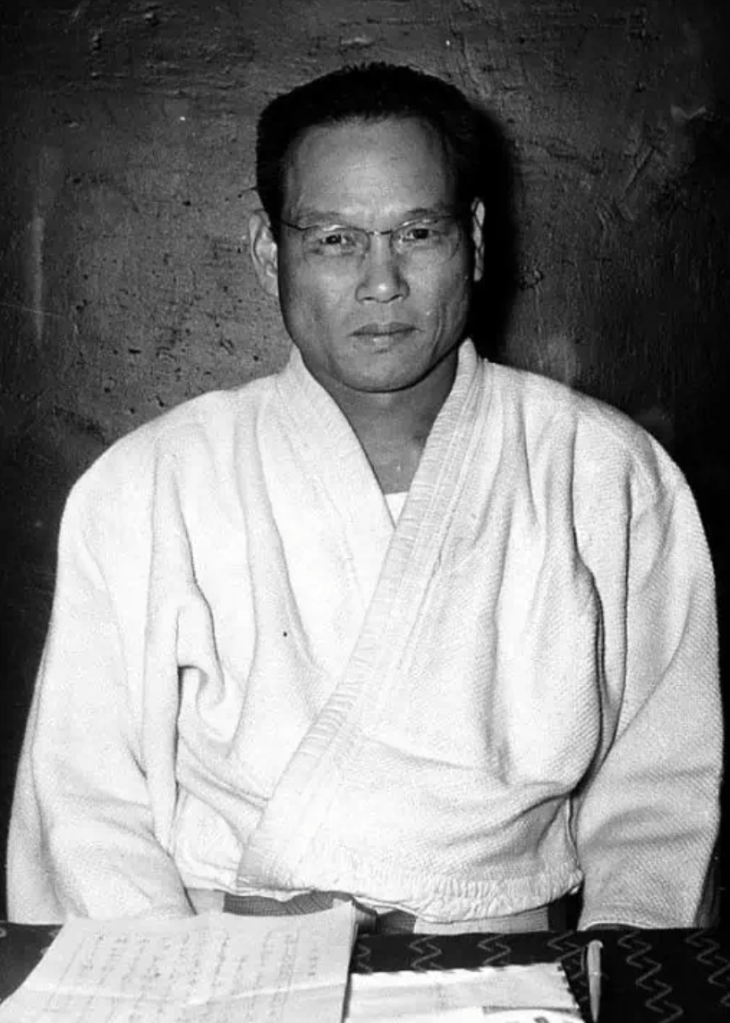

Tomiki began practicing judo from elementary school and distinguished himself in Waseda University’s judo club, obtaining his 4th dan rank while still a student. After his university years, he began studying under Morihei Ueshiba, who was establishing himself as independent from Daito-ryu Aiki-jujutsu. This connection with Ueshiba would continue throughout his life.

After graduating from university, Tomiki worked at Tohoku Electric Power and then taught for three years at Kakunodate Middle School. In 1929, he represented Miyagi Prefecture in the Imperial Martial Arts Tournament. Later, to intensively study Ueshiba’s techniques, he moved to Tokyo and lived close to Ueshiba’s dojo, training intensively for two years.

Philosophical Development and Teaching in Manchuria (1930-1945)

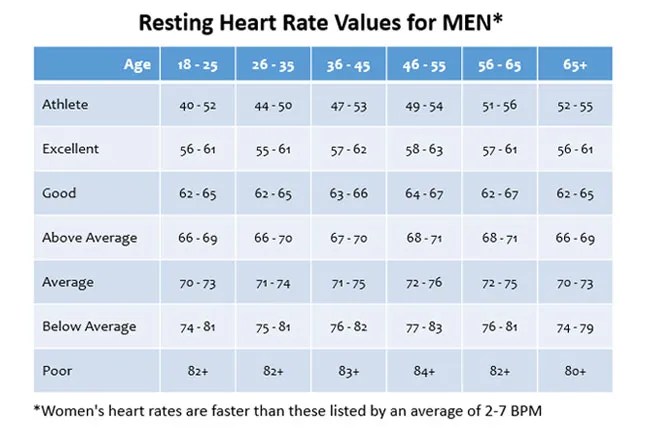

In May 1928, Tomiki wrote a letter to Kaizan Nakazato expressing his views on martial arts. He identified shortcomings in Kodokan Judo compared to Daito-ryu, particularly noting that judo practitioners experienced decline in ability after age forty, while Daito-ryu’s subtle breathing power seemed to remain effective into old age. He also observed that Kodokan Judo was extremely limited in scope due to competitive rules, while Daito-ryu was unrestricted and aligned better with swordsmanship and spearmanship principles.

In 1935, Tomiki traveled to Manchuria where he introduced aikibudo to Hideki Tojo, then commander of the Kwantung Military Police. This led to teaching positions at the Kwantung Army Military Police Training Unit, Daido Academy, and the Shinkyo Police Department from 1936. In February 1939, he became an associate professor at Kenkoku University.

On February 11, 1940, Ueshiba implemented a dan ranking system, granting Tomiki the first 8th dan in aikibudo. The following year, in April 1941, Tomiki also received 6th dan in judo. During this period at Kenkoku University, he worked to systematize, theorize, and popularize Aikido, with the goal of eventually making it competitive.

Teaching Style and Philosophy

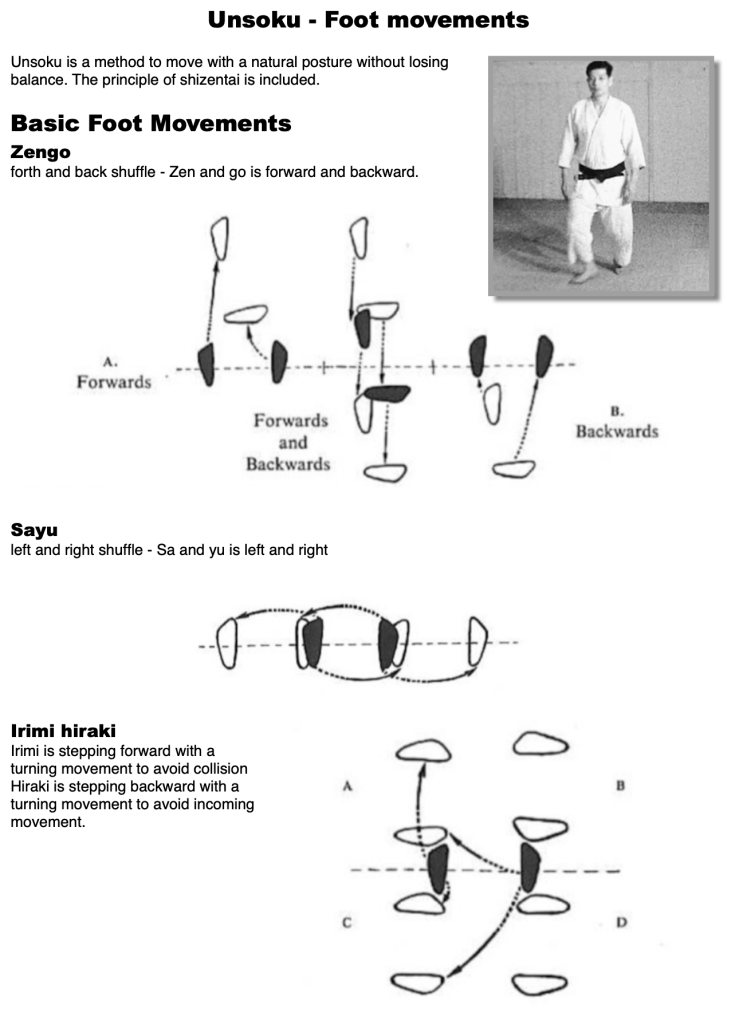

Tomiki’s teaching approach at Kenkoku University was described as “rationalist” compared to Ueshiba’s “irrationalist” method. While Ueshiba’s teaching emphasized intuition, embodiment, and enlightenment without detailed explanations, Tomiki focused on theoretical and systematic instruction. He explained the mechanics of techniques through principles like shizentai no ri (natural posture), kuzushi no ri (balance breaking), and ju no ri (flexibility).

Students characterized Tomiki as gentle, mild-mannered, with “warm, soft, large hands.” He was described as always smiling, with a solid build but extremely gentle demeanor. Despite sometimes appearing “cold at first glance,” he was surprisingly attentive to his students, even bringing home-cooked meals to hospitalized students.

Tomiki was not only accomplished in martial arts but also in traditional Japanese arts. He enjoyed dancing and would teach students the Sado Okesa dance. He was talented in calligraphy and painting, particularly in creating ink paintings of bamboo. This artistic ability came from training with his uncle, the Japanese painter Hyakuho Hirafuku.

Theoretical Contributions

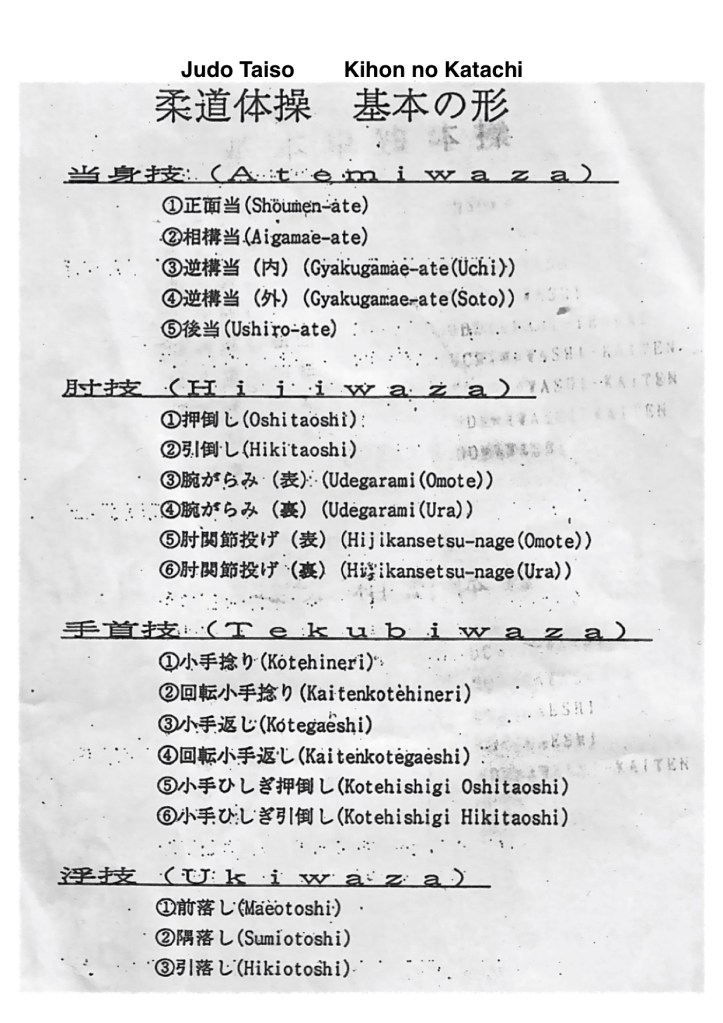

Tomiki developed a systematic theoretical framework for aikido, connecting it to Jigoro Kano’s achievements in modernizing jujutsu. He named techniques with descriptive terms like “oshi-taoshi” (push down) and “hiki-taoshi” (pull down) rather than using jargon, making the art more accessible. He emphasized the connection between martial arts and other Japanese arts, noting that the principles of body and power were common across disciplines like kabuki, dance, calligraphy, and painting.

In his 1954 book “Judo Taiso,” Tomiki explained his rationale for systematizing aikido techniques. He noted that while judo had successfully reorganized throwing and ground techniques (randori techniques), there was still a need to develop a structured approach to atemi-waza (striking techniques) and kansetsu-waza (joint techniques). Through his 30 years of study, he recognized the deep connection between judo and aiki jujutsu principles.

By 1943, Tomiki had published works exploring the relationship between form and principle in martial arts. He explained that principles could only be understood through techniques and forms, emphasizing the importance of kata training and referencing the Buddhist stages of shu-ha-ri (preserve, break, leave). He connected martial arts principles to Chinese painting theory, particularly the concept of “bone method,” concluding that understanding these principles allows one to “respond to circumstances and changes, and work freely without hindrance.”

The “Bone Method” Concept in Tomiki’s Martial Arts Philosophy

The concept of “bone method” (骨法) is a profound philosophical principle that Kenji Tomiki incorporated into his martial arts theory, drawing parallels between traditional East Asian painting theory and martial arts practice.

Origins in Chinese Painting Theory

The “bone method” originally comes from traditional Chinese painting theory, specifically from the “Six Laws” (六法) of painting established by Xie He in the 5th century CE . In this classical framework, the Six Laws include principles like “spiritual resonance and life movement” (气韵生动), “bone method and use of brush” (骨法用笔), and other technical aspects of painting.

Tomiki’s Application to Martial Arts

Tomiki adapted this concept to martial arts in his writings on “Form and Principle” published in 1943. In these texts, he explains that the “bone method” in painting parallels the fundamental principles that exist behind martial arts techniques. Just as the “bone method” gives structure and life to a painting, the underlying principles animate martial arts techniques.

According to Tomiki, “spiritual resonance and life movement” represents the life essence of painting, while the other five laws (including bone method) are means to bring this life movement to the painting. He saw a direct parallel to martial arts, where the visible techniques express deeper underlying principles.

Practical Meaning in Martial Arts

In practical terms, the “bone method” in Tomiki’s martial arts philosophy represents:

- Essential Structure: Just as the bone structure gives form to a body, the “bone method” provides the essential structure to both painting and martial arts techniques.

- Freedom Through Structure: Tomiki concludes that “Only those who understand the bone method can freely express their conceptions on paper. It is like those who understand the principles of martial arts can respond to circumstances and changes, and work freely without hindrance.”

- Beyond Mere Technique: The concept suggests that true mastery goes beyond learning shapes or movements, requiring an understanding of the underlying structural principles that give life to technique.

Connection to Tomiki’s Overall Philosophy

This concept reflects Tomiki’s broader approach to martial arts as a systematizer and theorist. By incorporating concepts from Chinese aesthetics into martial arts theory, he demonstrated his intellectual breadth and his commitment to placing martial arts within a larger cultural and philosophical framework.

The “bone method” exemplifies Tomiki’s rationalist approach to martial arts, where understanding the fundamental principles (the “bones”) allows practitioners to express techniques with both structure and freedom, adapting fluidly to changing circumstances.

Post-War Years (1945-1948)

After Japan’s defeat in 1945, Tomiki was detained by Soviet forces at Lake Balkhash in Siberia. This internment lasted three and a half years, during which time Manchukuo collapsed and Kenkoku University closed. Tomiki finally returned to Japan in late 1948.

During his internment, Tomiki continued to refine his understanding of martial arts. In the preface to “Judo Taiso,” he mentioned that his experiences during internment clarified the significance of maintaining traditional techniques while adapting them for practical use. Upon his return to Japan, he would further develop his systematic approach to aikido techniques.

Legacy and Impact

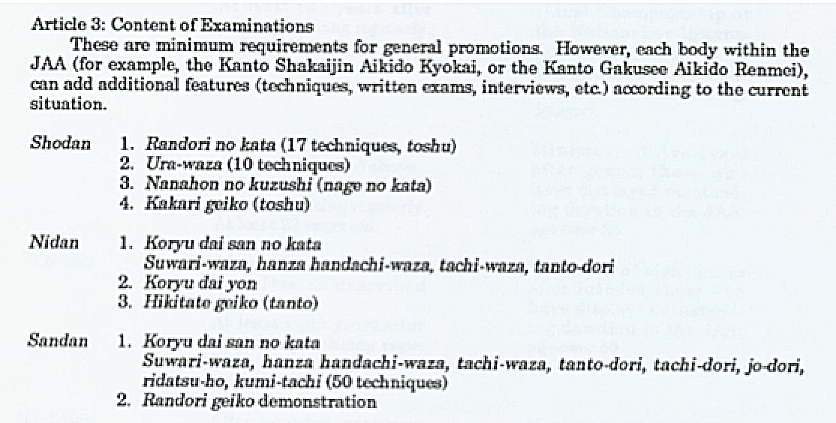

Tomiki’s contribution to martial arts centered on his synthesis of traditional aikijujutsu with modern educational methods. He established a system to teach striking and joint lock techniques rationally, making them accessible within the framework of physical education. His approach created a bridge between the irrationalist, intuitive training methods of traditional martial arts and a more systematic, principle-based approach suitable for modern education.

Tomiki viewed his work as continuing the legacy of Jigoro Kano, who had successfully adapted traditional jujutsu into modern judo. Similarly, Tomiki sought to transform the “aikido techniques” of Morihei Ueshiba into a structured educational system, preserving their essence while making them accessible to contemporary practitioners.

This period from 1900 to 1948 represents the formative years of Tomiki’s development and his initial contributions to systematizing aikido. His later work at Waseda University would further develop his vision of competitive aikido, creating a distinct branch within the aikido world.

Summary of Source Materials on Kenji Tomiki

The materials provide comprehensive documentation of Kenji Tomiki’s life, philosophy, and contributions to martial arts, focusing on his development of a systematic approach to aikido. Here’s a summary of the key documents:

1. “Kenji Tomiki Budoron” (Document 1)

This extensive text appears to be Tomiki’s major philosophical work on martial arts, containing chapters on the uniqueness of Japanese martial arts, modernization of budo, judo principles, and aikido development. The document explores how traditional martial arts can be adapted to modern educational contexts while preserving their essential character. Tomiki articulates principles like shizentai no ri (natural posture), ju no ri (flexibility), and kuzushi no ri (breaking balance) that form the foundation of his technical system .

2. “Judo Taiso” (Document 7)

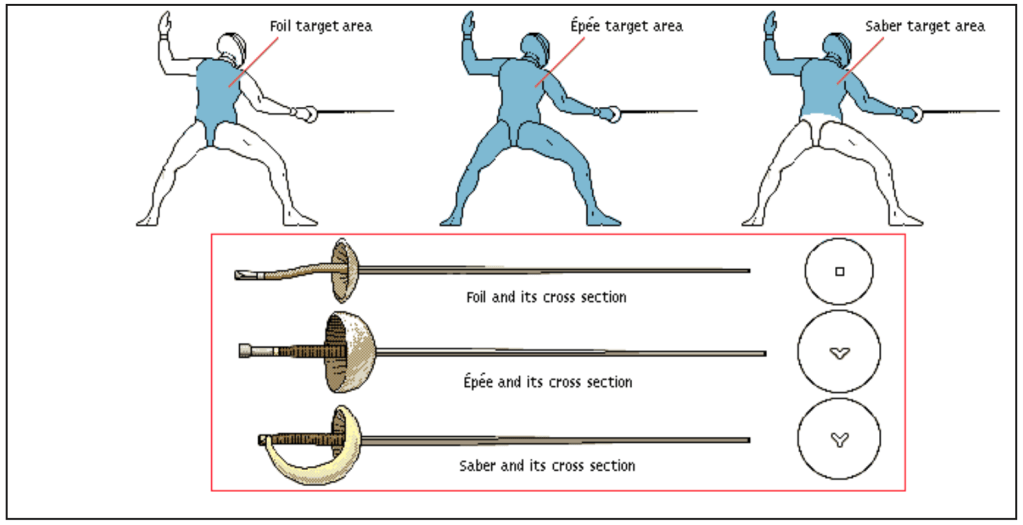

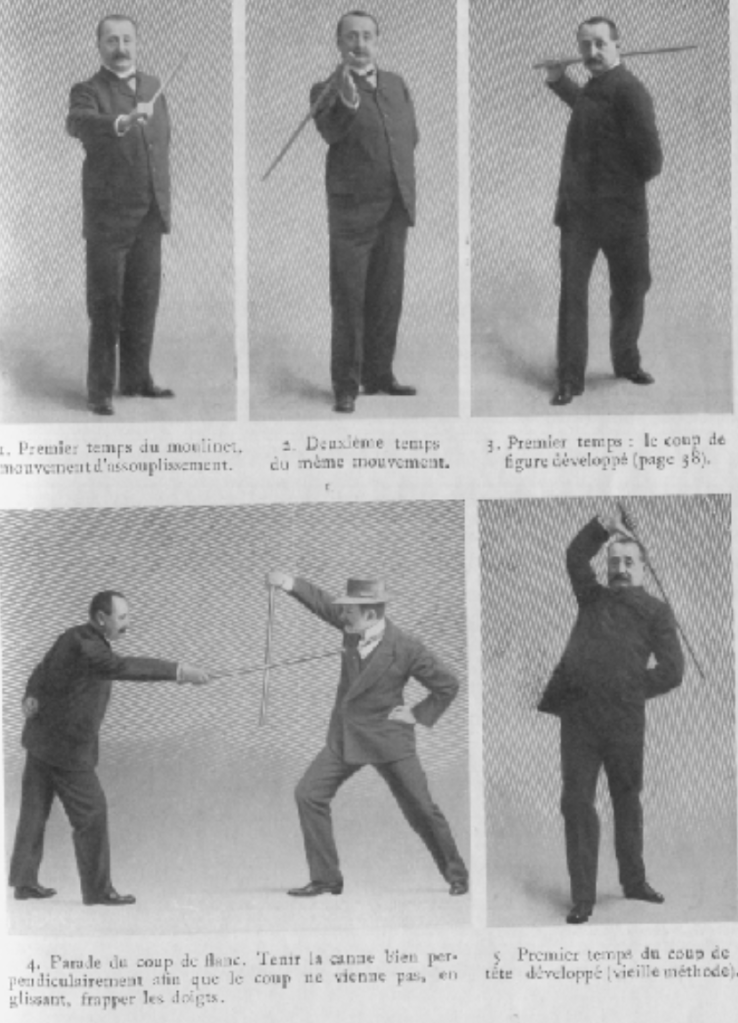

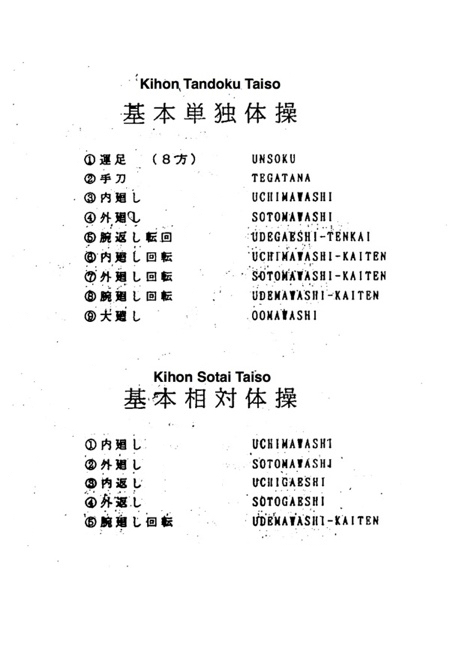

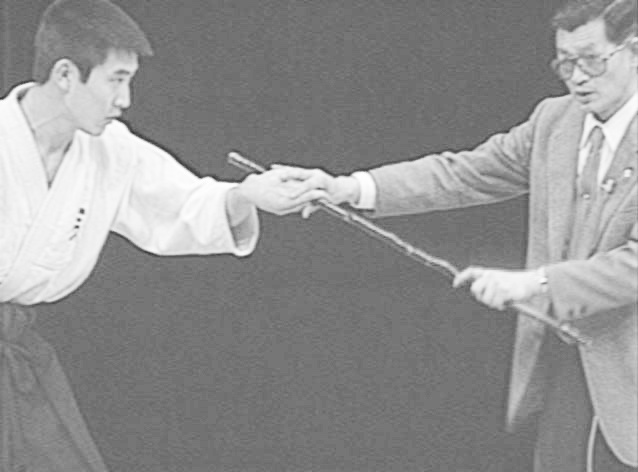

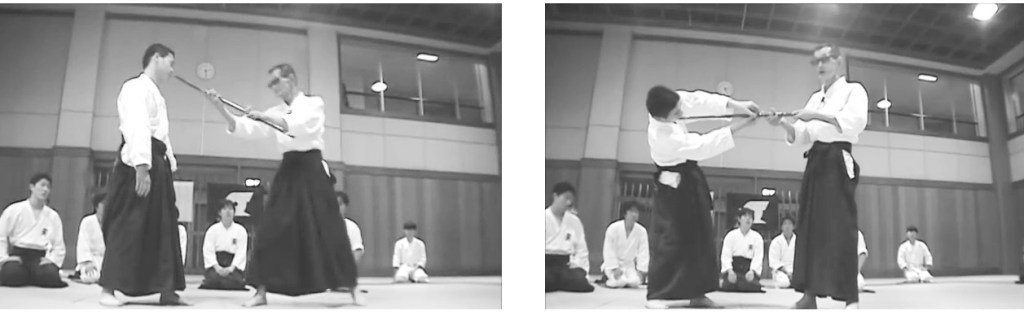

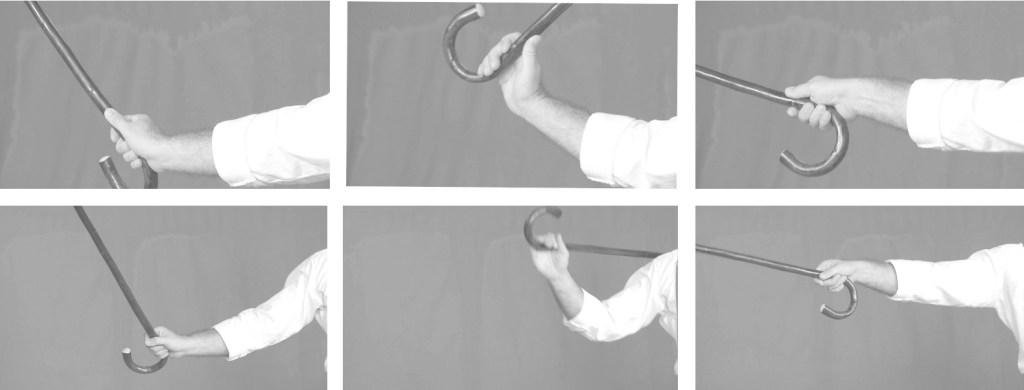

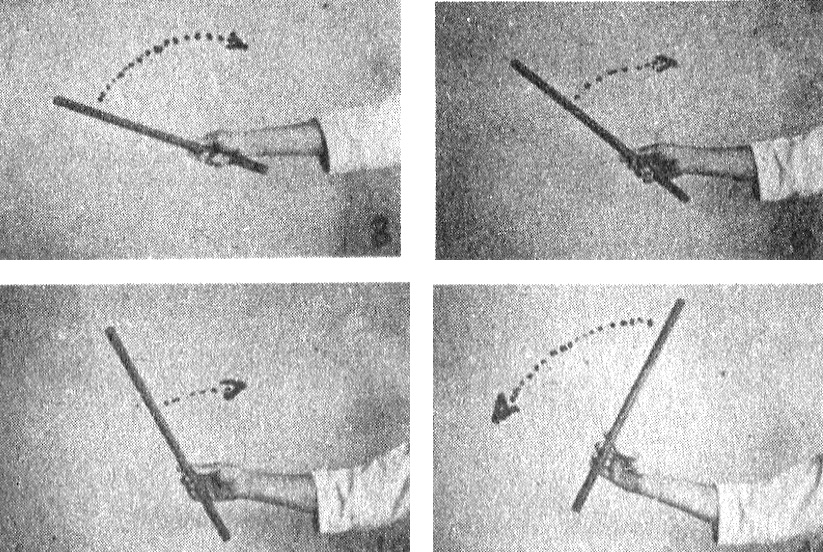

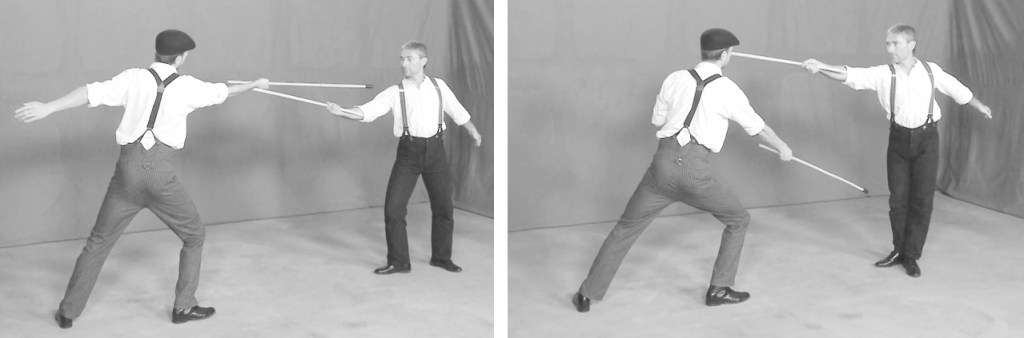

This translated work from 1954 details Tomiki’s system of “Judo Exercises” that apply judo principles to aikido techniques. He explains how he reorganized striking and joint lock techniques from Daito-ryu Aiki Jujutsu into an educational framework. The document includes detailed instructions for basic movements, postures, and techniques with accompanying illustrations .

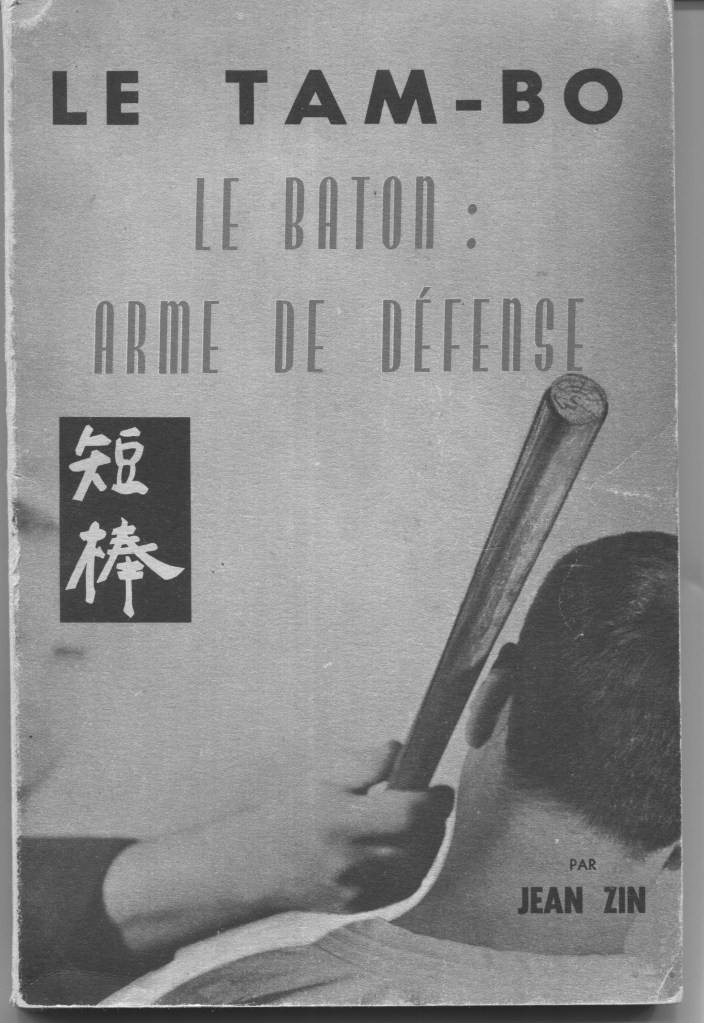

3. “Aikido Nyumon” (Document 8)

Published in 1958, this “Introduction to Aikido” provides a rational method for practicing striking and joint lock techniques. The document outlines fifteen basic forms and their applications, continuing Tomiki’s systematic approach to aikido instruction with detailed explanations and illustrations .

4. “Personal Views on Martial Arts” and “Prewar” (Document 9)

This document contains Tomiki’s 1928 letter to Kaizan Nakazato expressing his views on martial arts and criticizing Kodokan Judo from the perspective of Daito-ryu. It also covers Tomiki’s time teaching at Kenkoku University in Manchuria (1939-1945), detailing his relationship with Morihei Ueshiba and his development of a rationalist approach to aikido instruction .

5. Key Terminology (Document 4)

This document provides definitions of essential concepts in Japanese martial arts, including philosophical terms like Bushido, technical concepts like kata and waza, and educational approaches like goraku (entertainment-oriented) and tanren-shugi (discipline-oriented) training methods .

6. Additional Supporting Documents

Several smaller documents provide supporting information about specific aspects of Tomiki’s work, including his views on competition in martial arts (documents 2-3), his approach to school martial arts education (document 5), and philosophical differences between recreation-oriented and discipline-oriented physical education (documents 3, 5) .

Together, these documents present a comprehensive picture of Tomiki’s life work: creating a bridge between traditional martial arts and modern educational methods by applying scientific principles, systematic organization, and rational teaching approaches to the techniques of aikido.