Dogmatism versus Evolution

Every martial art that respects itself must not cling to dogmatic thinking. Japanese martial arts often use “kata” to practice fundamentals. However, many kata have become so formalized that etiquette and choreography have become more important than the original fundamental principles they intended to convey.

We encounter the same perspective in Western martial arts, which often also employ dogmatic approaches to gain legitimacy. This dogmatic thinking regularly forms a barrier in the evolution of both the martial art and the practitioner.

Modern science has extensively described many elements in the context of sports practice, thereby elevating various sports to a higher level. Take high jumping, for example: the technique used is certainly tested against developments in modern biomechanical science of human movement.

Modern Scientific Concepts

Examples of a modern perspective:

- Rhythmic and repetitive movements: Natural oscillations

- The natural adoption of optimal positions and movements: Attractor states

Natural Oscillations

Natural oscillations in martial arts refer to rhythmic, repetitive movements that naturally occur in the human body and in interaction with an opponent. These oscillations are essential for:

- Efficiency

- Balance

- Timing

- Force generation

They arise from the dynamics of the body, gravity, and interaction with the environment (e.g., the opponent).

The Oscillation versus Cartesian Dilemma

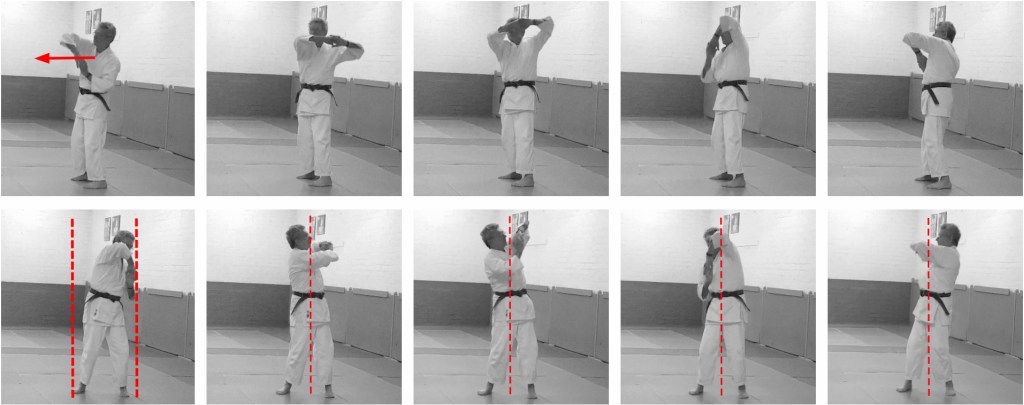

Natural oscillations create movement patterns that are inherently adaptive. Japanese kata or formal forms are an example of this, provided they encompass this concept.

Cartesian patterns, on the other hand, are linear-geometric: straight lines, fixed angles, circles, spirals, or static positions. These create rigid motor programs that are difficult to adapt when the opponent does something unexpected.

The Transfer Paradox

Oscillation-based kata develops dynamic invariants – underlying movement principles that remain stable while surface expression varies. A spiral movement can manifest as a strike, deflection, or evasion, depending on the context.

Cartesian kata teaches specific motor sequences that allow little variability. It becomes a catalog of “if-then” rules instead of fluid adaptation.

Attractor States

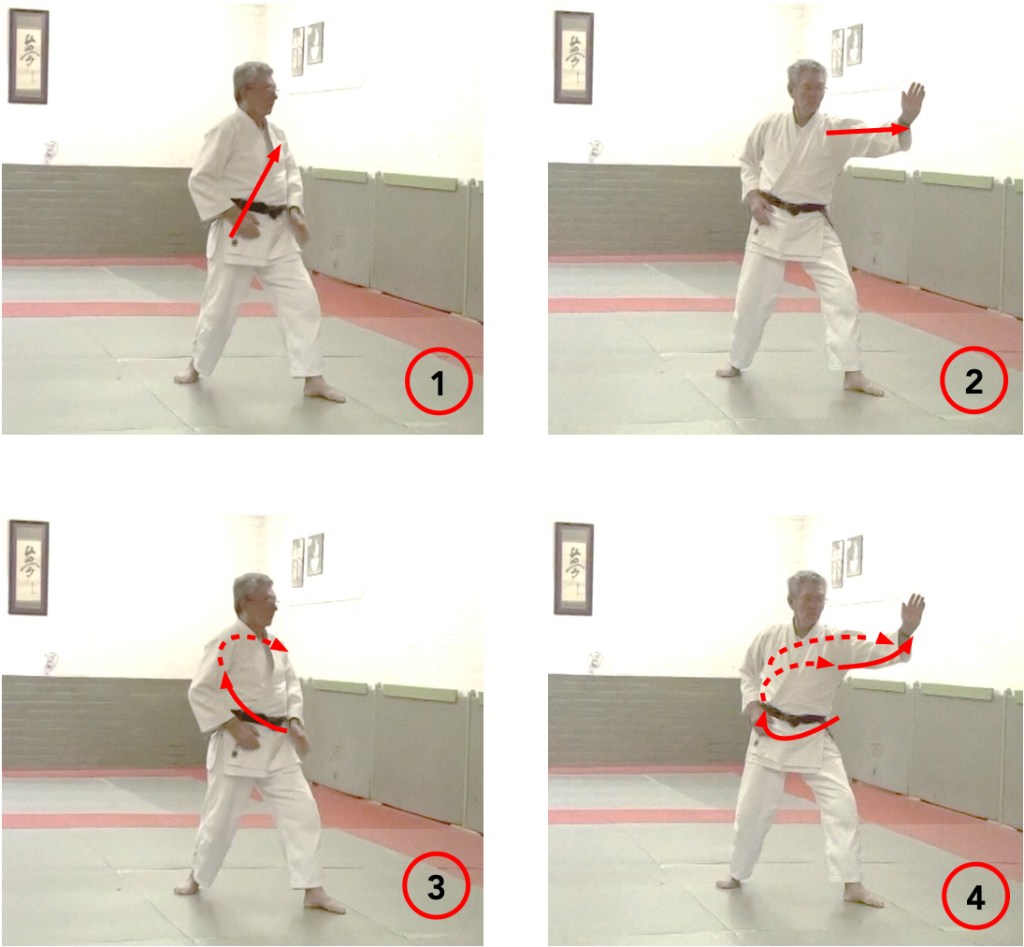

In martial arts, “attractor states” refers to a concept from systems theory and movement science. The idea is that the human body and our movements naturally tend toward certain efficient, stable, or optimal patterns. These patterns are called “attractors” because they essentially “attract” and stabilize movements, even with small disturbances.

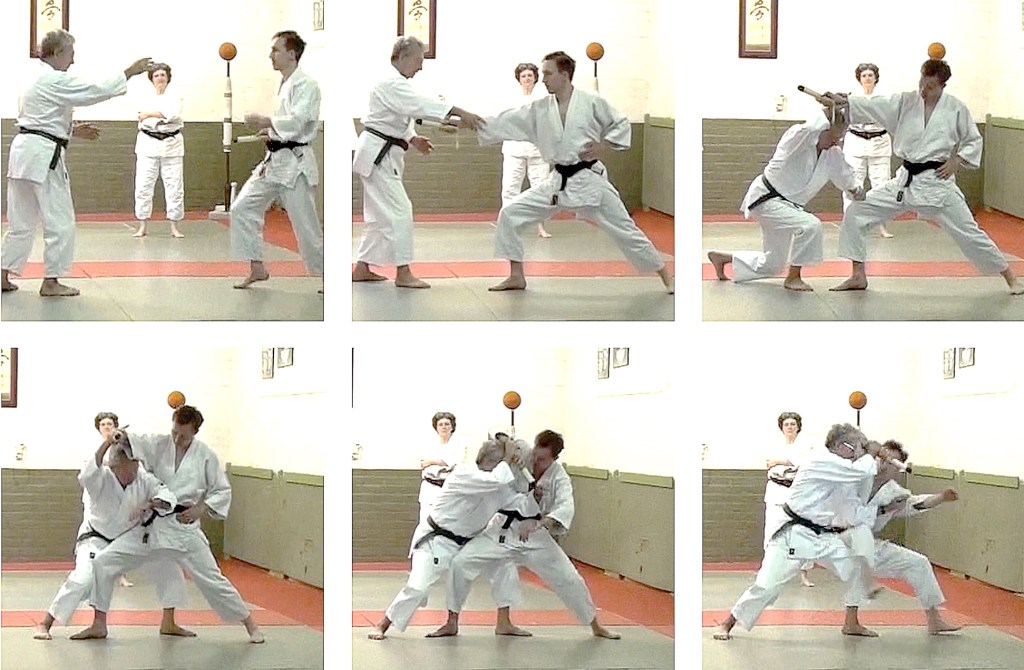

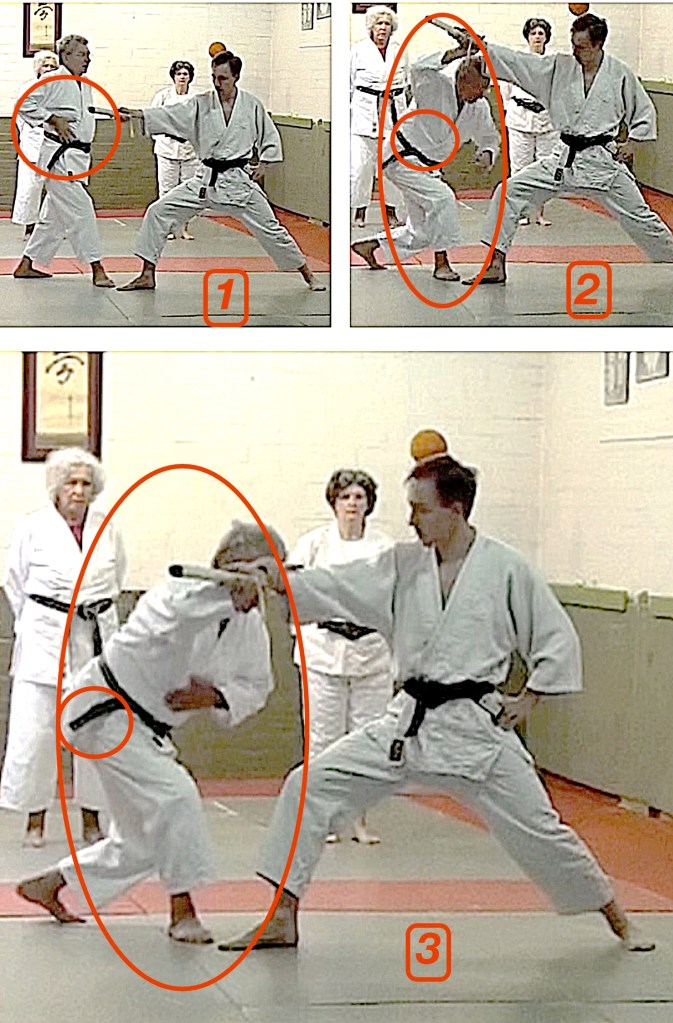

Attractor States in Tomiki Aikido

In Tomiki Aikido, attractor states are primarily formed through:

Repeated randori: By continuously practicing against resistance, practitioners develop natural, unconscious reactions that are most efficient. These reactions become attractor states: they feel natural and are the result of selection under pressure.

Economy of movement: In randori, you quickly learn which movements cost the least energy and are most effective. These movements become the “attractors” in your repertoire.

Adaptability: Tomiki Aikido encourages adapting techniques to the situation, making attractor states not rigid, but flexible and context-dependent.

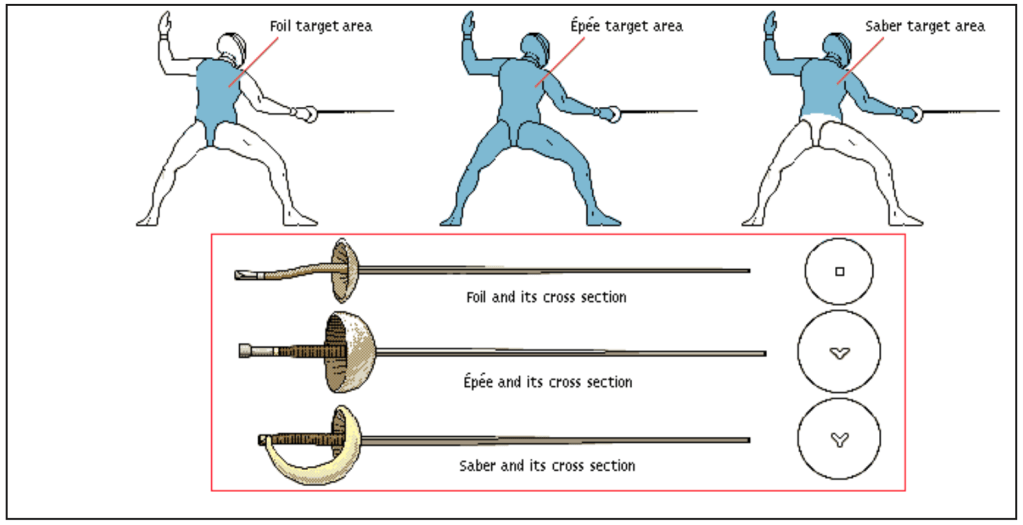

Western Martial Arts: La Canne as an Example

La Canne—the French stick fighting art—is an excellent example of a Western martial art where the principles of natural oscillations and attractor states are just as applicable as in Eastern combat sports.

1. Natural Oscillations in La Canne

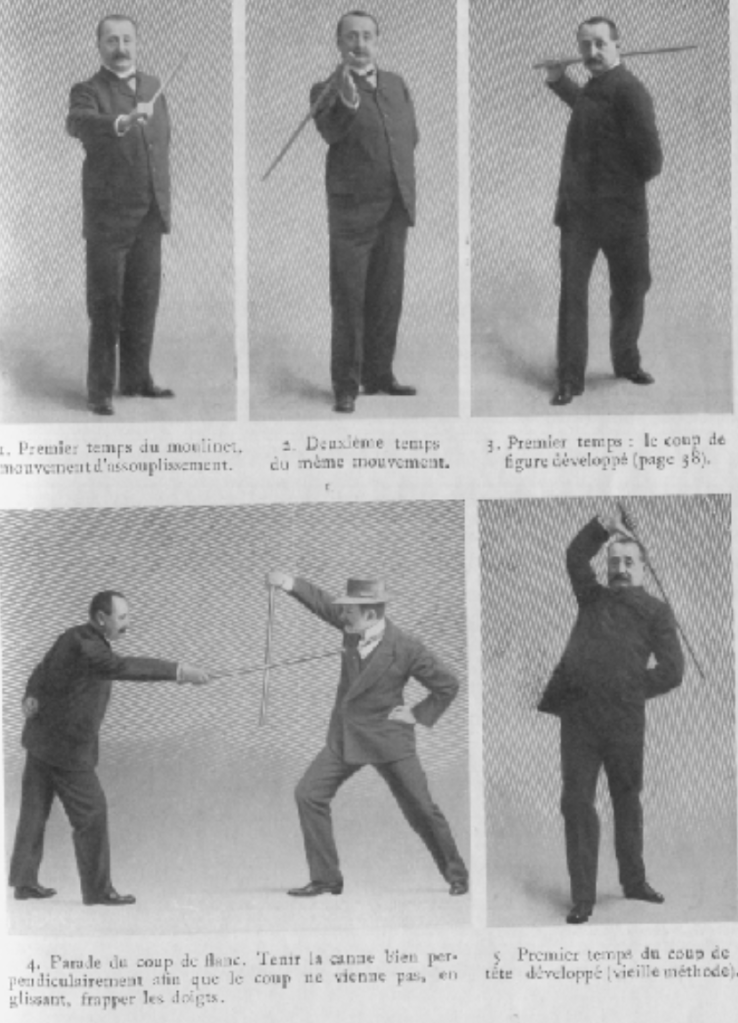

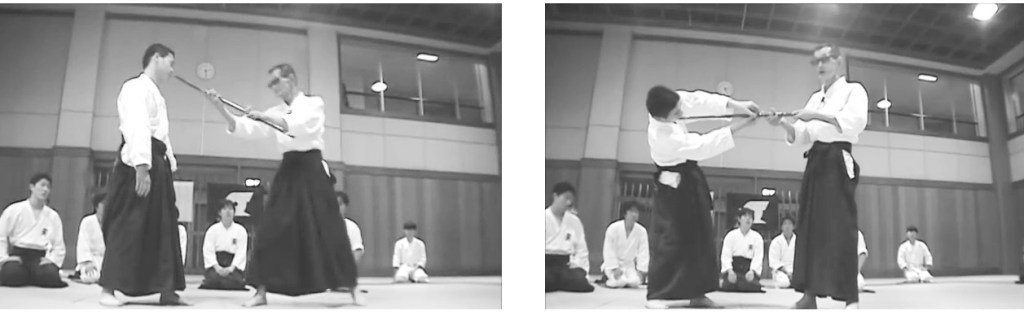

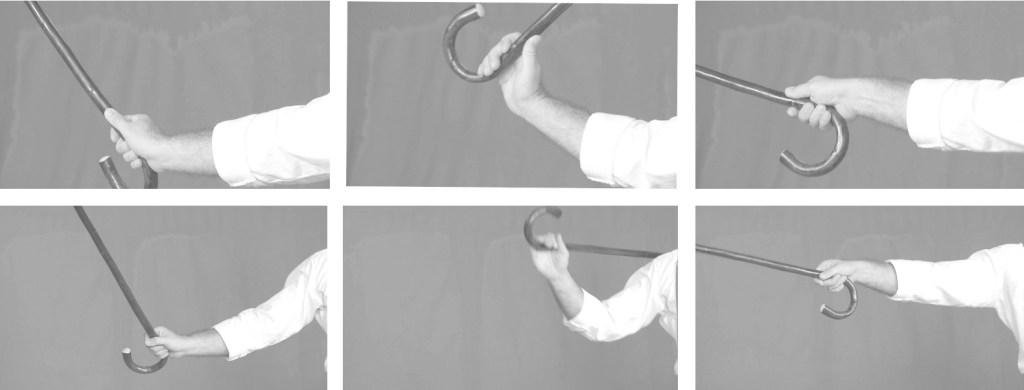

a. Rhythmic Stick Movements

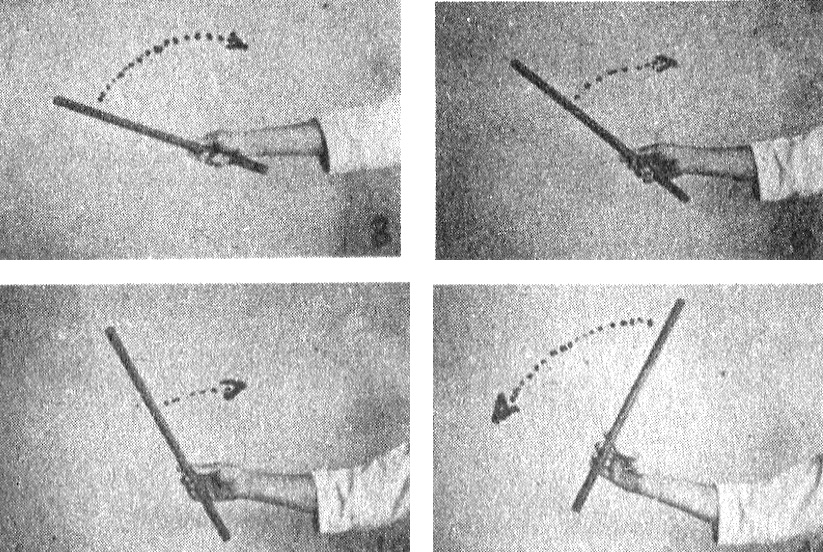

What: The stick is not handled statically, but in flowing, rhythmic movements (oscillations). This helps maintain momentum, move the stick faster, and mislead the opponent.

How: For example, continuously executing positions between high and low postures or performing brisés (downward stick swings) and enlevés (upward stick swings).

Example: A classic moulinet (windmill) is an oscillation that can be employed both defensively and offensively, helping to keep the stick in motion without interruption.

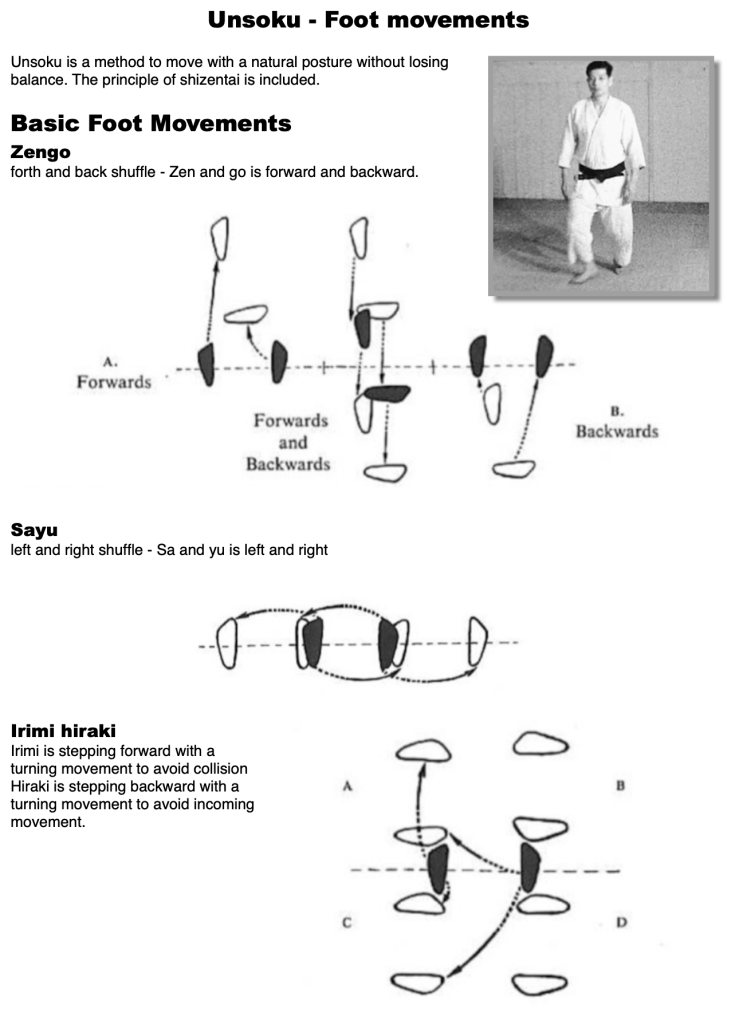

b. Footwork and Body Movement

What: Footwork in La Canne is often oscillating: small, rhythmic steps forward, backward, and sideways that help maintain balance and quickly change direction.

How: By moving the body and stick in a natural rhythm, the practitioner can react faster and generate power from the hips and shoulders.

Example: Rhythmically shifting weight from front to back leg during attack or defense, making stick movements smoother and more powerful.

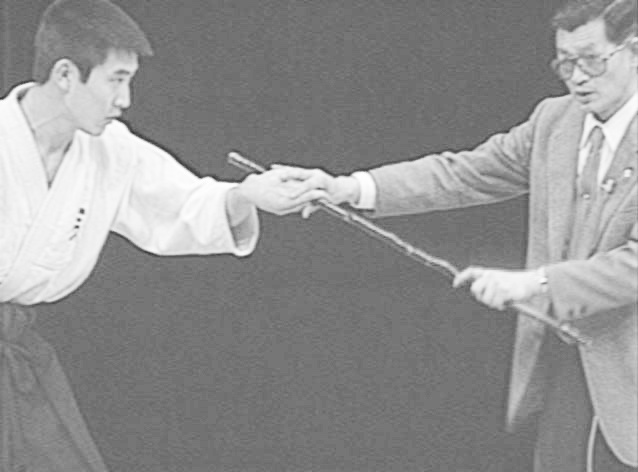

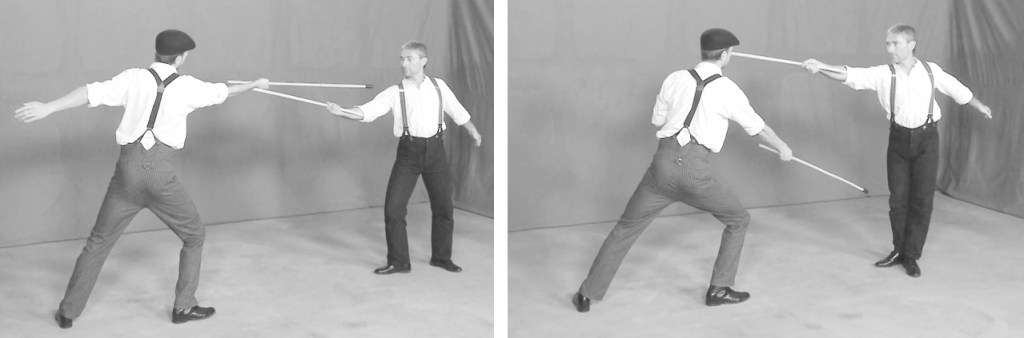

c. Timing and Counter-oscillation

What: Using the opponent’s natural oscillation to evade or interrupt their attack. This is comparable to the principle of “kuzushi” in Japanese martial arts.

How: By observing the opponent’s rhythmic movements, a La Canne practitioner can attune their own oscillations to this and strike or deflect at the right moment.

Example: When the opponent makes a large strike, the practitioner can step inside with a small, rhythmic movement and place a quick thrust on an uncovered area.

2. Attractor States in La Canne

a. Natural Postures and Positions

What: The natural adoption of optimal positions and movements that the practitioner automatically returns to. These postures provide balance, protection, and power.

How: Through training, the body develops a preference for certain positions, such as a slight forward lean with the stick in a neutral position, ready to strike or deflect.

Example: The “garde basse” (low guard) is an attractor state: the stick is held low, ready to react quickly to an attack.

b. Automatic Reactions

What: Through repetition, certain deflections and attacks become unconscious, natural reactions—attractor states that are most efficient under pressure.

How: For example, when someone makes a thrust to the head, an experienced La Canne practitioner will automatically make a deflecting movement and immediately launch a counterattack, without having to think about it.

Example: A “parade” (deflection) followed by a “riposte” (counterattack) is a classic attractor state in La Canne.

c. Efficient Movement Patterns

What: Attractor states are also the most efficient movement patterns that cost the least energy and are most effective. These patterns are selected and reinforced through training and sparring.

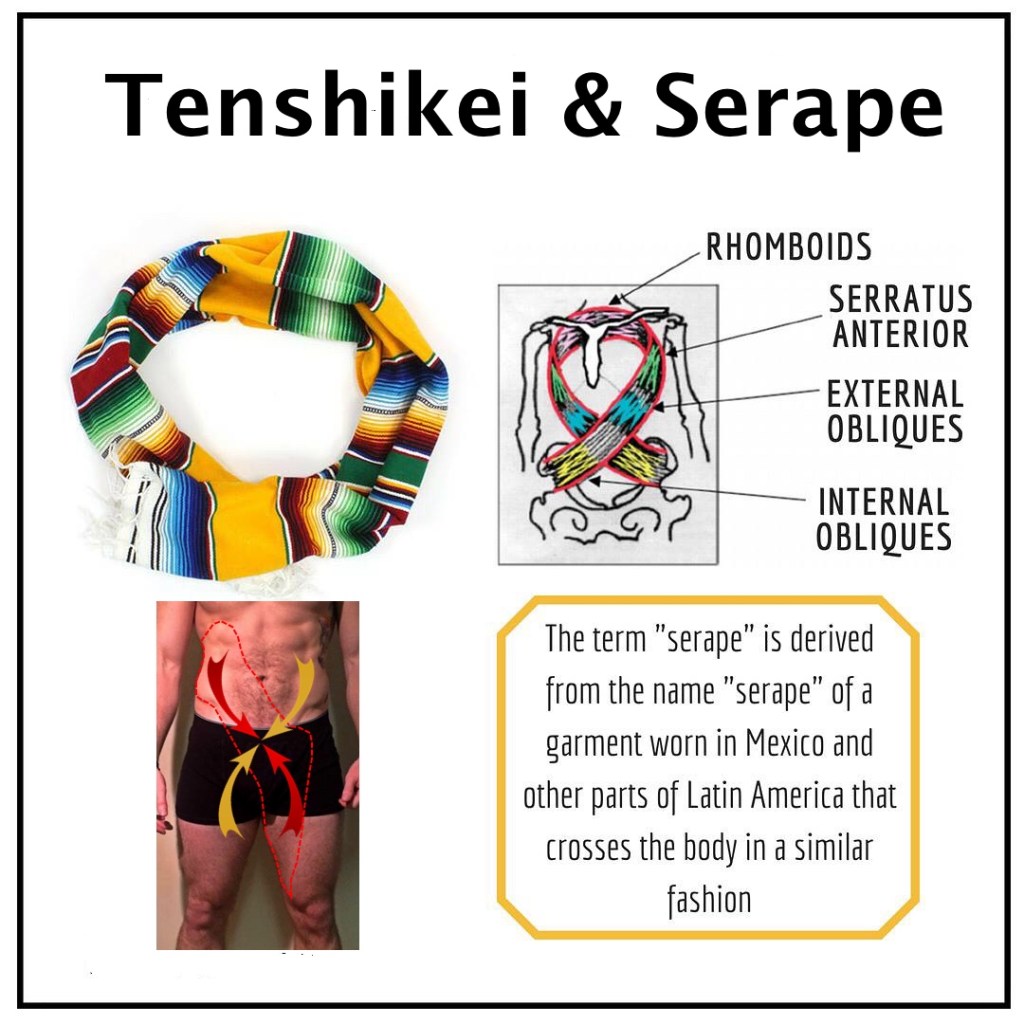

How: For example, using the hips and shoulders to generate power instead of just the arms, making stick movements more powerful and faster.

Example: A moulinet preceding a brisé strike is an attractor state because it’s a natural, efficient way to generate power with the stick.

Application in Training

- Practice rhythmic movements: Begin by rhythmically swinging and rotating the stick, combined with footwork.

- Train under pressure: Sparring helps develop attractor states, because only the most efficient movements work under pressure.

- Observe and adapt: Pay attention to your opponent’s natural oscillations and use these to improve your own timing and reactions.

- Repeat basic techniques: By repeatedly practicing basic techniques, they become attractor states—natural, unconscious reactions.

Adapting Formalized Forms

It is naturally a challenging task to adapt a formalized form, designed by the founder or creator of the martial art, to modern scientific insights. There often exists a form of dogmatic thinking that prohibits questioning the ideas and words of the founder.

In Tomiki Aikido, there exists the basic kata—also called randori-no-kata—which describes the techniques that may be applied during “shiai”. It is remarkable that many practitioners are not creative enough to use other techniques not appearing in the kata as openings for a technique that does appear in the basic kata.

Forward-Looking Questions

Why wouldn’t we design new kata or reform an existing kata into a more profound series adapted to modern scientific findings?

Possible approaches:

- Biomechanical optimization: Restructuring kata around natural oscillations

- Variability training: Integrating multiple execution forms per technique

- Pressure testing: Developing kata that transfer better to free practice

- Neuromotor principles: Consciously cultivating attractor states in form training

By integrating these modern insights, we can preserve the wisdom of traditional kata while enhancing their effectiveness for modern practitioners.